Richard Butler | Exclusive Report By Harriet Cook of Linguisticator | NOV 10th, 2020

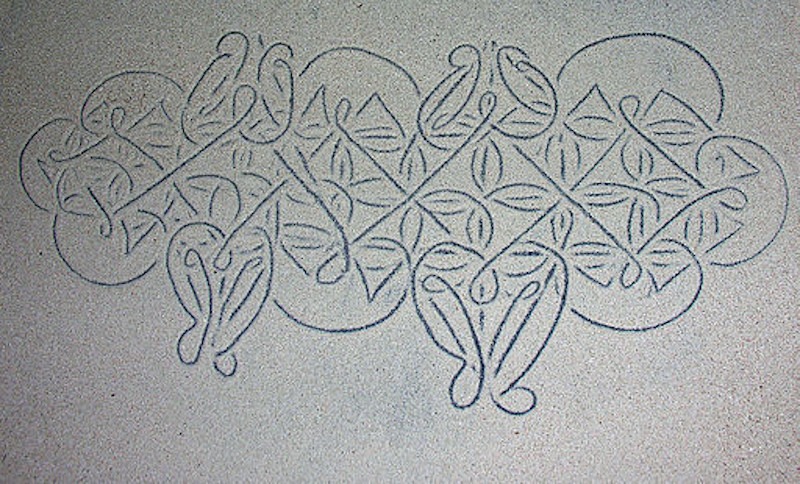

Sand, volcanic ash and clay are all used on the Vanuatu archipelago as canvases on which to inscribe meaning. What might appear to be intricate drawings at first glance are in fact complex geometrical patterns used to tell a story or transmit a message.

In the same way that Silbo Gomero is unintelligible to the untrained ear, the meaning of Vanuatu sand drawings can evade those with untrained eyes. It is only those well versed in the Vanuatu sand drawing tradition that are able to make, read and interpret these interwoven designs.

The tradition of sand drawing on this Pacific island nation has been inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2008. Stephen Zagala, whose PhD work focused largely on Vanuatu, prepared the file nominating Vanuatu sand drawing for inclusion on the list. His enthusiasm and passion for Vanuatu sand drawing are particularly clear in a paper published online four years prior to UNESCO accepting the tradition as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage; we will return to this paper later on in this post.

However, before focusing on Zagala’s work and his proposals for how this tradition might be protected in the future, it is important to establish what exactly Vanuatu sand drawing entails. Since including Vanuatu sand drawing on their Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, UNESCO have published a video that talks in a considerable amount of detail about what they call Vanuatu’s ‘unique and complex tradition of sand drawing’.

UNESCO briefly touch on the history of Vanuatu sand drawing, noting that it was first developed as a means of communication that served to connect the central and northern islands of Vanuatu where over 80 different language groups exist. We can therefore suggest that Vanuatu sand drawing started off as a kind of universal language that enabled communication between people living on the same island nation.

However, UNESCO highlight that this is a ‘multifunctional form of writing’ that serves not only communicative purposes, but also ritual and contemplative ones too. Indeed, the video explains that the drawings can be used as mnemonic devices that record and transmit ritual as well as mythological lore and information about local customs.

In his paper on Vanuatu sand drawing, Zagala calls into question the convention of calling this tradition ‘sand drawing’, preferring to think of it as a kind of writing. To support this view, he notes that the indigenous words used to speak about this tradition on Vanuatu are the very same words used to describe European writing. His paper also provides more detail on the origins of Vanuatu sand drawing, highlighting that they developed as ‘a form of communication and symbolic exchange’ within what he calls the ‘dynamic cross-cultural environment’ that was product of the archipelago being home to around 80 different language groups.

After highlighting how sand drawings were understood across these language groups and gave way to ‘cultural exchange’ no longer limited by language barriers, he goes on to explain how sand drawings simultaneously serve as a means to establish ‘cultural distinction’. This tradition is one that is locally specific, with both UNESCO and Zagala underlining just how important the tradition is for transmitting local information, be that a community’s history or a message that needs to be shared with a specific group of people.

In the conclusions to his paper, Zagala talks about the challenges the Vanuatu tradition of sand drawing poses to heritage management, highlighting that ‘simply creating an exhaustive catalogue of sand drawing designs would be to disregard and potentially destroy intimate processes of concealing and revealing information through performance of this tradition’.

His discussion ties in nicely with Julie Mitchell’s essay on cultural tourism and intangible heritage. In this essay, Mitchell considers what happens when tourists take photos of sand drawings and whether the action of taking photos constitutes a form of appropriation of indigenous cultural heritage. She raises these questions as Vanuatu sand drawings are by very nature ephemeral, disappearing as soon as a gust of wind blows over them. If you’d like to read more about the kind of measures being put in place to ensure that the Vanuatu communities have control over the photos and videos that are taken and put online, you can find her essay here.

While tourists are welcome to see performances of sand drawing at the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, there are also lots of efforts made to celebrate and preserve the tradition within the local community. Edgar Matasanuvi, the protagonist, is a master sand drawing artist from Pentecost who is transferring his skills to a younger generation in Saturday classes. In the short video, he speaks with pride about the Vanuatu sand drawing tradition, revealing that it is their way of communicating and also a part of their identity

Mislav Popovic, in a short piece on this tradition, highlights other ways the Vanuatu sand drawing tradition is being preserved, noting that there are now sand drawing festivals held in Ambrym, Ambae, Malakula, Paama and Vanua Lava, revealing an ever-increasing interest in celebrating Vanuatu sand drawing.

With locally-led initiatives like these in place as well as support from UNESCO, it seems that the tradition of Vanuatu sand drawing will continue to flourish. As Zagala highlights in his paper on Vanuatu sand drawing, the term ‘intangible heritage’ is key to the survival and preservation of this tradition. Precisely because of its ephemeral nature, documentation alone, while important in terms of preserving and sharing knowledge, is not enough to save the tradition and is, in some cases as described by Mitchell, somewhat inappropriate. It is, however, of undeniable and crucial importance that communities on the Vanuatu archipelago continue to pass the tradition from generation to generation, educating each other about it, celebrating it and sharing it with the worldwide community as they see fit.