– Vanuatu from Radio New Zealand

This content is from the Collections section.

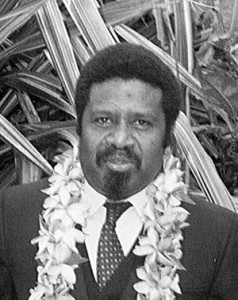

WALTER LINI – PRIME MINISTER

Born on the island of Pentecost, Walter Lini (1942-1999) studied for the Anglican priesthood in New Zealand. He became leader of the New Hebrides National Party (later Vanua’aku Pati) and his country’s first prime minister on independence in 1980. He was re-elected in 1983. In 1991 he lost his party’s leadership and stepped down. Under his leadership Vanuatu supported the Kanak indigenous movement in New Caledonia and was the only Pacific country to support the right of East Timor to self-determination. He was interviewed by Ian Johnstone in 1994.

-

Father Walter Lini ( 35′ 5″ )

Walter Lini became leader of the New Hebrides National Party (later Vanua’aku Pati) and his country’s first prime minister on independence in 1980. Under his leadership Vanuatu supported the Kanak indigenous movement in New Caledonia and was the only Pacific country to support the right of East Timor to self-determination. He was interviewed by Ian Johnstone in 1994.

TRANSCRIPT

Ian Johnstone: I’ve heard it said that Vanuatu is the only Pacific country that had what you could call a negative, totally negative colonial experience. Did you feel that at that time?

Father Lini: I felt it at the time. It became more clear when in 1960 the Americans came and bought plots of land, lots of land and subdivided it. When the landowners and when the ni-Vanuatu, but mostly members of the Advisory Council were beginning to question why the French and the British were doing this, then even though every session of the Advisory Council the question would be asked, the question was never answered.

We were sitting there and everyone was sitting there but the land was being taken away from under our nose and it was clear that there was no political power and the French and the British were not going to do it for us so they let it happen legally. They tried to make it a legal deal with the Americans but obviously the churches and the people of Vanuatu, even the missionaries who were in Vanuatu, were totally against what was happening. So I guess that was another thing that influenced.

IJ: But they carried on. Who did you try to persuade that this is wrong, the French, or the British, or both?

WL: The British. Mainly because I was able to communicate with them because I knew enough English to be able to be able to speak with them. The person in charge of the Anglican church at that time was also a member of the Advisory Council, the Arch-deacon who then became Bishop. So we tried to discuss it with him. We put our thoughts together so that he could take the feeling and the thinking of our people to the Advisory Council. He was the one who was outspoken against the whole land sale that had been taking place, and subdividing the land.

IJ: Was it dangerous to be outspoken in those days?

WL: It was very dangerous to speak, but it was perhaps easy for an Anglican leader of the church to do it… even a missionary, an Archdeacon who was there, I don’t think the British would touch him, or the French would be able to touch him so it was right that he should do it.

IJ: Yes, rather like South Africa. You must have been so angry, perhaps even more angry with the British. After all here they were hastening Fiji to independence, ready to move in Gilberts, ready to move in Solomons, but not in your case.

WL: Yes, it was sad for us to see that but we began to understand that because it is a condominium, the British cannot do it on their own. So it also began to dawn on us that the British would be willing to give independence to the New Hebrides but the French were clearly totally against independence of the New Hebrides.

So when politics began for me in 1970-71 it was clear that I would try and push, to put before the British District Agents our thoughts and ideas through English language and through other British administrators and British missionaries who were in Vanuatu or New Hebrides at the time.

IJ: Can I just ask Father, who was ‘us’? Had you formed the National Party or Vanuaaku Party by now?

WL: We formed what we called the New Hebrides Cultural Association, this was decided upon Queen’s Birthday 1970. It was at the cocktail hour. Three or four of us who were educated here in New Zealand, and we had already started this Western Pacific Students Association, and some of the thoughts we had started here. We stood there together and drank a whole length of a time for the cocktail. We realized everyone had already left!

The British Commissioner came and almost chased us out, so when we went out we said okay, we will start tomorrow, we will work for a political, we will change the, we will form a Cultural, a New Hebrides Cultural Association. That was in May.

IJ: How long before it did become a political movement, and how did that happen?

WL: It became a political movement three months after it was formed. Because we had a meeting and then we considered everything that we did was not enough for an association to raise and to question and to put forward, and we even thought that it would be better to form a political party to support what the members of the Advisory Council were demanding from the French and the British administrators at that time. So in September we became a political party, New Hebrides National Party.

As soon as we call it the New Hebrides National Party then every other people including other people in other places too, understood that there was a political group, because our cultural association was not clear. So we maintained the party as the New Hebrides National Party. We wait until 1976.

Then we began to discuss that maybe the French and the British now know and are sure that we have political aims and political party that we have set up here cannot be questioned. They already know it as a political party.

IJ: So they knew what you were doing. How were you able to get your word out? Presumably radio and newspaper wouldn’t report what you were doing?

WL: We had small pamphlets, about 16 pages, the first one called the New Hebridean Viewpoint. We continued to call it New Hebridean Viewpoint until in 1966 it became clear to us that the only way that we would be able to deal to the French and the British at the time is to change the name of the party, so they wouldn’t understand what it means!

IJ: So that’s why Vanuaaku is… So it was a piece of camouflage.

WL: So we changed the name, we had a congress at Tauto on Malakula, we decided on various proposed names, and then we came up to Vanuaaku Party which in fact means the same, it means the National Party. Our main effort, our main emphasis at the time, was to try confuse the British and the French, so they wouldn’t know what Vanuaaku Party means.

IJ: Now is it round about this time that the government of national unity was spoken of? Were you that far along?

WL: No we were… in 1977, there was supposed to be an election, then we decided that we would not participate.

IJ: Because?

WL: Because we were totally against going to Paris and London to meet and Vanuaaku Party said that we would meet in Vila, not in Paris or London.

IJ: So you refused to go. But the others had, hadn’t they? The Fijians went to London.

WL: Yes, the others had. And even our opposition, UCNH, and union of moderate parties went. They even bought our plane tickets, they worked out allowances for us in London, we all went and collected it. At the time of boarding the plane we refused to go. So the others went.

IJ: Had you decided that beforehand? Was that a piece of disobedience that would make its own point?

WL: It would appear it’s a piece of disobedience, but we decided that we would not go. We emphatically told them that it is very important to hold a meeting in New Hebrides because we are discussing New Hebrides. We should not hold it in London or Paris. So we stood by that and those who went to Paris and London and decided on a date of election, and then election came, we also boycotted the election, saying that if not enough people go to polls, it will be difficult to set up a government. So they went to elections and then the government could not work.

IJ: What did you do in terms of telling your people? Did you actually encourage civil disobedience? “Do not do what this government asks”?

WL: Yes.

IJ: Who did you learn that from?

WL: I don’t know! In fact we had some influence from Western Samoa, some knowledge of what had happened in Western Samoa. That is the only place we would have said we had learned from what had happened in Western Samoa at one time. So we took that stand and we decided not to go to elections and not to… instead we would declare a provisional government.

And so when we declare provisional government, we paralysed all the services that the government can carry out in the rural areas. Even, we would not allow the government officers, especially the British Government officers to go, and we arrested a number of British District Agents. One in the Banks Islands, another in Tanna. We held them and then we let them go again after discussion, at the threat of arresting all of us we let them go!

IJ: You smile about it now, Father, but this is civil disorder, this is treason! What was it like then? You were risking imprisonment, all sorts of things.

WL: Yes, we were. It was good, we were in Vila, we did not hide on one of the islands, we were in Vila and we did everything and we communicated everyday with the government, both the French and the British. I was in Vila so sometimes I would call the British Resident Commissioner to talk with him, or one of his officers. The French, I’d talk to him and his officers.

At times when I sensed that maybe if I go to that meeting then they’d arrest me, because one time I rang a famous radio person of the time named Jean Masias, he was French head of that department. He was the head for the whole of Radio Vanuatu. So I rang him and said I have some news I want to report to you, so I said I want to come and give it to you in the office. He said, no, don’t come to the office but I will be waiting in a car at such and such a place with one other officer. Then as soon as I put down the phone I said to my other two people who were supposed to go and see him, “We shall not go”. Because they refused to see us in their office, we refused to see them in their car. We will not meet them on the road. If we meet them on the road maybe they will listen to what we say, if not they will kill us or they will arrest us. So we didn’t go.

IJ: This has got strong anti-colonial elements in it. Did you feel in danger ever, of your own life? And the other members of the party?

WL: The other time which was very tense was when we decided to bring a radio into Vanuatu.

IJ: A transmitter?

WL: It came in the plane through the Immigration, passed. As soon as we put that suitcase in a taxi we reach the point where we had all the people ready, one to pick it up, next to pick it up and run with it, next we were at the point where we could hide it. It was very tense at that time, when the person who was bringing it came through Immigration, and then passing through. As soon as it was placed in the car, in 15 minutes it was in the place where we wanted it to be! You can say it’s a kind of treason against the established government – but we had to do it.

IJ: So no problems? What was the priest saying to himself while all this was going on?

WL: I thought it was quite justified because I think I was doing it for the right of the people.

IJ: Had there been changes to the then running but still colonial constitution? That was Father Leymang as chief…

WL: That was what put Father Leymang in. He was Prime Minister and I became his Deputy.

IJ: So you were part of that election?

WL: Yes, of Father Leymang. But it was not an election, it was just a government established by negotiation, to get some members from our side, and some members from theirs.

IJ: So now your conditions had been met for the discussion of a constitution. The three main concerns were land, citizenship, and decentralisation. What did you decide about each of those issues in the constitution?

WL: We decided that because of the experience that we had with the New Hebrides Identity Card, it was alright to have that identity card, but in a number of places we were not accepted. We also knew at that time that there were people like the French, who had dual citizenship. So when we looked at the constitution, we decided that it would be very important for us to have only one citizenship. If you are going to have a Frenchman wanting to become a ni-Vanuatu citizen, he has to renounce his French citizenship. Or the British or New Zealander or – so it was just one.

IJ: Land? All foreign ownership of land, what did you decide about that?

WL: We decided that – it was one of the key points of our constitutional discussion was to make sure that all lands in Vanuatu returned to the custom owner, to make sure that the Americans and all the other people who bought the big masses of land would not take this land away, it would still be ni-Vanuatu.

IJ: That would be the most controversial of all, the most difficult, the most likely to put you into major trouble I would have thought, with the ‘colons’ and with the existing government. But you weren’t going to compromise?

WL: We were not going to compromise. And we were glad that it was agreed on by every political party. Even though the other political parties were against independence, in as far as land was concerned –

IJ: That was your trump card really, wasn’t it? And decentralisation, what did that mean? Giving authority to the other islands?

WL: Yes, that was the very last point to agree on, because the French and the francophone parties insisted that we shall not agree to the constitution until it is clearly indicated that before independence is granted, we have to have a government of Tafea in the south, and a government of Santo, it has to be worked out before, and if it is possible, we can do that before we get independence. That was in the constitution.

So we tried from 7 o’clock in the morning until it was 7 at night, we couldn’t agree on that point, so we continued until the next morning, about 5 o’clock we decided okay, we’ll sign the constitution. We agreed on the constitution. The cocktail that was prepared for us in the French Residency, when all the guests were there at 7 o’clock waiting for everyone to go including the members of the UN observing team, all the dinner and cocktail was wasted, none of us went to eat …

IJ: Exhausted! Afterwards you wrote and thanked the British and the French, I think your phrases were ‘for their patience and tolerance’. Were those just the normal courtesies you pay, I mean were you in fact angry while that process was going on?

WL: I was at times angry. But sincerely, I thought the patience that the British and the French had was in fact sincere. Because in a way the French and the British in fact did not do anything to develop us. In fact they waited, waited and waited until we saw, ourselves, how we should begin to move to get self-reliance, no, self-government and independence. It was not them forcing us, but our people demanded it from them. In fact I thought that we went to independence because we really wanted it, not because it was forced upon us.

IJ: So in a way their opposition and their inability to do anything, their neglect of you, was to your advantage because it made you decide. I understand that point. It can’t have seemed like that then though, you must have felt like pawns, were you?

WL: During the time of the work-up to elections it was that time, and after elections that I became more frustrated with the French and the British. I became more mad with what the French were trying to do. Because all the delays had been mostly by the French. We would sit in, for example, in a Security Council, which was me, the French Resident Commissioner, and the British, and we would agree if there was a situation of order, law and order, developing in one of the islands, we would agree, the British would send their police immediately, the French would drag their feet and then maybe instead of sending it before the morning, in the middle of the day they’d say “Oh we’ve decided not to send police forces”. So those were the incidents or the cases that really made me much more madder. I became mad because the French were deliberately trying to tell us lies and deliberately trying to show that they were in control, not us.

But when the situation developed in Santo, with Jimmy Stevens, then we had to deal right away with it. The French and the British were still there, and I was really frustrated when we were able to get the British Army, the British Marines to come and stay there, and then the French brought theirs to Vanuatu too, but they wouldn’t do anything.

So my experience of having UN forces or different governments’ forces as a peacekeeping force in a country which has an internal problem, it would be very difficult for the police or the security forces to take an action. Especially if someone who is overall commander of the forces has a completely different view and wants to direct the things the way he wants not for peace but perhaps to continue…

IJ: Indeed, yes, for his own motives, which were different. You must have felt a great sense of disappointment as well. Here was the nation achieved, unity, and moved into a constitution, with the – not necessarily enemies, but certainly people outside from outside – you’d overcome them, and here within you, as it were, was Jimmy Stevens. What would you like to have done with him?

WL: Jimmy Stevens is a very nice person to talk to, but he’s a very devious man. He’ll tell you one thing but immediately after you go, he will do something else. I became more dissatisfied when we would work on a programme of work with the British and the French and when we’d finished, the French would send their own person to talk with Jimmy Stevens and then they will come with what Jimmy Stevens had said to tell us.

IJ: So you were still victim of all kinds of… Did you ever feel that your country might fracture?

WL: Yes, at one point we did… until when we sent the British and the French back then we got the PNG forces to come in with the Australians, to give us the backing, then we were able to give direction… saying, this is what we want, then the PNG people will carry out, but when the British and the French were there we would not be able to do that.

IJ: A significant change itself… you’d become then a Pacific power, or a Pacific country, truly. Did you feel a sadness that the resolution of Nagriamel and all that, was to put this man into jail?

WL: Yes, I felt sad that that was so, and a number of times I would, personally, would release him, but my fear is that if we begin to do that, the constitution and subsidiary laws that have been made to govern the actions of individual political leaders or whatever will begin to erode the respect for law and order… for actions of treason will no longer be respected so even though as a priest I felt we should forgive Jimmy Stevens and all his followers for what they had done, again I questioned whether governments are there to forgive.

I resolved that governments are not there to forgive. The churches and individual persons are there to forgive, but the governments are there to make sure it is upheld, the law, and it is seen to be providing justice for all.

IJ: I’ve heard it said, from people like yourself who’ve fought the struggle to achieve independence and then taken a major part, that gaining independence is in a sense easier than making it work because you’ve a common cause, a common goal, and it can be difficult once that goal is achieved. Did you find that?

WL: Yes, that is true because we had a common cause, we wanted to make sure we do not lose our land in Vanuatu, that’s why we struggled and we were able to unify the whole population, of New Hebrideans then but today ni-Vanuatu.

So it was easy to achieve independence because we did not want to lose our land but we also wanted to have a constitution to protect our land and all the things that we have. But it was more difficult to govern because we had not experienced the art of decision-making, quick decisions that will have quick results, long term results, decisions that are very important for national security…

We did not have any experience in that and that is why, after we became independent, I went to Ratu Mara and asked him “Sir, I put the question to you – what are your views in running a country after independence? What are the most important things you must do?” He said “Only two. One – make sure you do not take a long time to make a decision. If you have to decide, decide. Secondly – if you find someone in your government is trying to slow down the decisions and the process of implementing what has been decided, get rid of him”. That was very useful because it helped me quite a lot.