Richard Butler | Science | April 21th 2016

Little is known about the Lapita peoples, the first settlers of the Western Pacific, other than their ubiquitous calling card: red pottery fragments with intricate designs. But in what’s being hailed as one of the most dramatic finds in years, researchers at the meeting offered a glimpse of the first-known early Lapita cemetery. “This is the closest we’re going to get to the first Polynesians,” says archaeologist Matthew Spriggs of Australia National University (ANU) in Canberra, a member of the excavation team.

The graves on Efate, in the Vanuatu Islands, are estimated to be 3000 years old. That’s around the time that the Lapita peoples began hopscotching across the Pacific from New Guinea’s Bismarck Archipelago, fanning out as far as Samoa and Tonga. The site reveals unknown facets of their burial customs, and DNA from the bones may offer clues to their origins. “The find has opened a new window on the Lapita people as a biological population as well as an archaeological culture,” says Lapita expert Patrick Kirch of the University of California, Berkeley.

Since the first Lapita shards came to light a half-century ago, more than 200 sites have been found, but skeletal remains are very rare. Then just before Christmas in 2003, workers quarrying soil for a prawn farm came across a chunk of pottery with a complex pattern. They showed it to a field worker with the Vanuatu Cultural Centre, Salkon Yona, who luckily had just been trained in Lapita identification. Yona consulted ANU archaeologist Stuart Bedford, who in a second stroke of luck was on the island for a wedding. Bedford confirmed the shard as early Lapita, skipped the wedding (“my friends understood,” he insists), and scrambled to protect the site, near Teouma Bay.

But the biggest surprise came when the team, led by Bedford, Spriggs, and Ralph Regenvanu of the Vanuatu National Museum, began excavating bones. Because so few Lapita burials had been found, the researchers assumed these were recent graves until paleoanatomy expert Hallie Buckley o f the University of Otago in New Zealand confirmed the remains were Lapita. Everywhere they dug, it seemed, was a skeleton. “It blew us away,” says Bedford. In two seasons, they excavated 25 graves containing three dozen individuals.

All skeletons were headless, a feature of other Pacific cultures. In some graves, cone shell rings were placed in lieu of the skulls, indicating that the graves were reopened after burial and the heads ceremonially removed, Bedford says. (The rings are 3000 years old, according to radiocarbon dating.) The heads were reburied. In one grave, three skulls (see photo, above) were lined up on the chest of a male skeleton, whose grave the bulldozers missed by centimeters. His bones bear scars of advanced arthritis. “He must have been in a lot of pain and was clearly looked after,” says Spriggs.

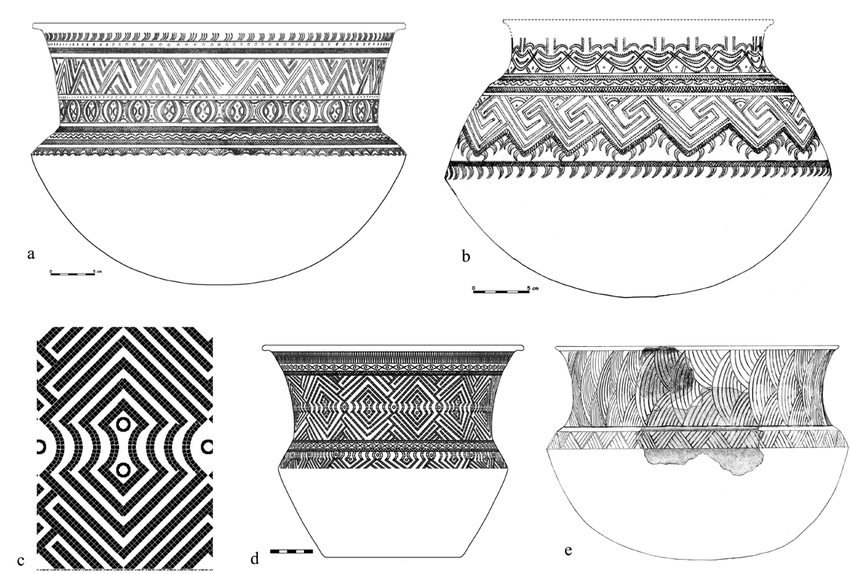

The pots too are revelatory. Some are burial jars, by far the oldest in the region. The inner rim of one features four clay birds peering into the vessel. The vessels are similar in form to early “red-slip” pottery found in Taiwan and islands of Southeast Asia, bolstering the argument that Lapita peoples at least tarried in this region on their eastward migration. An article on Teouma is in press in Antiquity.

After excavations this summer, the team hopes to extract DNA from bones to compare with modern populations. In the meantime, Teouma has become the pride of Vanuatu, which has featured its Lapita heritage in a set of postage stamps.